Information Security - Next Steps in Identity for UK Police Forces

With the recent Police National Database (PND) and Identity and Access Management (IAM) initiatives a number of Police forces chose to deploy local IAM technologies, integrated with the Central Services PKI infrastructure and accredited by the ‘Scheme for Police’ standard, instead of the 'Managed Service' offering. Forces that have deployed local IAM technologies are able to take advantage of some intriguing capabilities including:

With the recent Police National Database (PND) and Identity and Access Management (IAM) initiatives a number of Police forces chose to deploy local IAM technologies, integrated with the Central Services PKI infrastructure and accredited by the ‘Scheme for Police’ standard, instead of the 'Managed Service' offering. Forces that have deployed local IAM technologies are able to take advantage of some intriguing capabilities including:

Advantages

• Provisioning of access to resources whether local, national, restricted, confidential, physical or logical

• For each user, a reduced number of credentials (user names, passwords, cards, PINs). Potentially even a single smart card & PIN for use across all of their entitlements.

• Self-service group management and Role Based Access Controls (RBAC)

• Self-service password and/or PIN reset.

This post explores how any Police force could extract more functionality from existing IAM/PND investments, and how the implementation of an end-to-end identity management platform could achieve the full potential of those investments, not just by providing access to specific applications, but the entire range of resources.

Bringing PND to life has meant significant efforts from the NPIA and each Police force. At the local level, forces have made significant investments in highly secure server rooms and client access-points to access the national confidential platform. Forces would benefit from further integration by having local PKI services with a “Cross CA” trust to the national PKI. Given this capability forces could utilise certificate services to provide access to services offered at the national level and also enable a higher level of flexibility at the local level for both confidential and restricted environments.

The Managed Service is an offering designed and built for a single defined purpose; to enable forces to authenticate to PND. Many have taken advantage of this in order to meet the deadlines for the end of the Impact Nominal Index (INI). While features may or may not slowly open up from the Managed Service, it is likely forces now find themselves burdened with a local confidential infrastructure, featuring many of the components necessary for the delivery of other restricted/confidential local/national applications, but unable to leverage them. These forces are likely to be looking at alternatives to provide more feature-rich services from their investments and support for further applications.

By taking a few critical steps, several capabilities could be enabled such as those listed at the start of this document and:

- Ability to integrate a much broader range of additional national/local confidential applications within environments built for PND

- Extend IAM functionality into the restricted environment, providing automated provisioning of restricted-level entitlements, such as Active Directory accounts, telephony accounts, email and others

- Achieve cost savings by significantly reducing person-hours associated with identity management across both restricted and confidential environments

- Improve service by limiting the number of user names, passwords, smart cards and PIN numbers each person requires; the panacea is a single card for personal identity, physical and systems access.

Identity and Access Management

There are many benefits in moving to a locally provided IAM model, but there are some implications to consider before setting out on the journey. Addressing these will ensure a faster, smoother transition and create opportunities for further efficiencies and cost reductions.

In the following section we take a look at some example scenarios and examine some of the challenges you may encounter when moving to a local IAM model.

Somehow we need to stop building and re-building custom plumbing and/or user account databases into every new application that comes along. But as we have seen, centralisation hasn’t typically happened, and even when it does happen, along comes a merger or acquisition to mess it up.

Somehow we need to stop building and re-building custom plumbing and/or user account databases into every new application that comes along. But as we have seen, centralisation hasn’t typically happened, and even when it does happen, along comes a merger or acquisition to mess it up.

As an example of a really simple IAM environment, let's take a pure Windows/Active Directory & HR set-up. As somebody joins the organisation, HR enters attributes about that person into the HR database. The Identity Management system (i.e. Microsoft Forefront Identity Manager 2010), recognises there is a new person in HR, and is programmed to create new accounts in Active Directory and the telephone directory. It also sends the manager an email with the user name and password. On the day the new person starts their job, the person is provided with their Active Directory user name and password. The person then authenticates to an Active Directory server (a Domain Controller) via their Windows logon. That same server also handles authorisation to resources such as printers, file shares and databases which have been configured with permissions based on Groups stored in Active Directory. Once authenticated, the user is given a ticket which includes a list of the groups they belong to, this controls access and entitlements.

Active Directory also stores some attributes about these people such as email address, job title, telephone number etc. When we talk of "Identity", we are talking about these attributes, and group memberships, logons and passwords ‐ it is (digitally speaking) who you are, and Authentication and Authorisation decisions flow from Identity. In these simple situations we have grown used to a seamless, single sign‐on experience. It would now be impractical to have separate logon processes for email, printers, file shares etc. so this is why logon processes need to be kept in check and guarded against “credential creep”, where new systems demand new logon IDs, but may not necessarily need them.

Challenging Boundaries

One of the most significant challenges presented by PND and the national PKI is the separate identity. It is subjected to stringent business controls and technical safeguards to ensure that only approved and vetted individuals are able to access PND data.

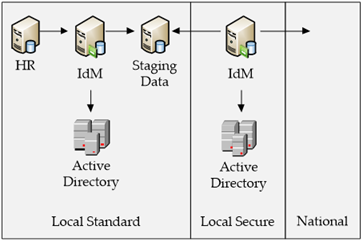

Police forces were advised to use a single source of identity, commonly assumed to be an HR database. If identities can be flowed from HR, through the restricted environment and then extracted from the confidential environment (effectively 'browse-down"), then the management of identities may be automated, integrating the necessary business processes such as requests, approvals and notifications. This is seen to a limited degree in the Managed Service, however that solution requires manual processes to create, manage and eventually remove each user – this is not true Identity Management and has the potential to create a huge administrative burden.

A Typical IT Environment

Within a typical environment most key business applications (HR, ERP etc.) have their own data stores for Authentication (user logons and passwords), Authorisation (attributes, groups, roles etc.), and image Attributes. At best this involves duplication, but sometimes data simply disagrees between systems.

Most Police forces will of course have some form of centralisation in place in order to tackle these challenges, so that the IT topology is not so much a bunch of completely independent ‘silos’ of identity but more ‘islands of identity’ where applications are grouped together to share a common set of credentials.

Most Police forces will of course have some form of centralisation in place in order to tackle these challenges, so that the IT topology is not so much a bunch of completely independent ‘silos’ of identity but more ‘islands of identity’ where applications are grouped together to share a common set of credentials.

We also see many examples where ‘home‐grown’ identity management solutions (for example involving scripts) have been developed to deal with the volumes of joiners, movers, and leavers. However, even the most sophisticated of these solutions suffer from drawbacks: They have often been developed with a very specific original scope in mind, rather than being part of a grand future‐proof plan; and they are often supported by the author who may or may not still be working for the organisation. These solutions also tend to provide point-to-point synchronisation with little or no orchestration or consistency between the different solutions.

Typically this situation results in: organisations spending more time and money on administration than they need to; potential security issues resulting from inadequate provisioning and deprovisioning control; difficulty in meeting governance, risk and compliance (GRC) reporting requirements; and a sub‐optimal user experience (for example multiple sign‐ons). In addition to all these challenges, this kind of situation makes it very difficult to cope with change, for example when rolling out new on‐premise applications and ‐ crucial to our subject here ‐ provisioning confidential Identities from the restricted level.

Introducing PND

To meet the expectations of the national accreditor and gain access to PND, it is conceivable that forces may have deployed Active Directory services independent of their existing installations, with new identities manually created during the Managed Service on-boarding process, purely to provide local users with access to the confidential platform. From there, smart cards delivered through the Managed Service would allow access to the PND application. By this stage, each single person will have one Active Directory user name + password for their normal computer, another Active Directory user name + password for their PND computer, and a Smart Card + PIN for the PND application. That’s a lot to manage for anybody, but an added challenge is that by its nature, this credential configuration also leaves smart cards open to abuse, and the range of credentials will be a burden on support costs.

Considerations and Challenges

To Fail to Plan is to Plan to Fail… it’s an old adage which is never more relevant than when organisations are looking to automate business rules and processes. If you take the ʺtypical IT environmentʺ and try to move some, or all users, from a manually provisioned state to an automatically provisioned state, and simultaneously add the confidential layer of identity management, you risk making the situation more complex. As a result there are some key questions and considerations that should be addressed:

- How do I manage user identities now and what will the impact be as those identities are migrated? Is my source data valid? Which business processes do I need?

- What are my deployment options? How do I stage provisioning users to each system?

- Can I support co‐existence? How do I synchronise identity data? How can I improve the user experience?

- What are the potential pit‐falls, and how do I avoid them? What is the most cost‐effective solution in the long run?

However, it is possible to identify some themes right away.

An optimal architecture will include a platform that brings together existing identity data (objects and attributes), and synchronises it based on business rules and policies. This can enable the automatic provisioning of new accounts based on an authoritative source (such as HR), and automatic ‘de-provision’ of old and unwanted accounts. In addition to direct improvements in administration, security and the user experience (due to synchronisation of authentication information resulting in reduced sign‐on), this platform is a solid base from which to launch new initiatives in an agile manner ‐ such as the issue of multiple identities and single card access for multiple accounts. It should be noted that Microsoft Forefront Identity Manager (FIM) 2010 is ready and able to be integrated with other industry systems such as (but not limited to) Oracle, SQL, SAP, ActivIdentity and PKI. So the implementation of a commercial off-the-shelf identity management platform, such as Microsoft FIM 2010 will facilitate this architecture.

It is important to point out that we recognise that identities must be maintained separately with distinction between confidential and restricted systems. But they may both be sourced from the same HR data, and both can be stored on a single smart card where other environmental factors allow. At least one design including this configuration was approved by the national accreditor. In cases where a single card may not seem possible for technical reasons e.g. restricted and confidential systems are accessed concurrently on distinct devices, then design modifications can be made either to provide two cards (still removing usernames and passwords) or a browse-down function from within confidential to restricted environments.

Similarly whilst single sign-on can exist in restricted and confidential, it cannot exist between the two in order to satisfy Code of Connection requirements.

Police budgets are under incredible pressure, and the substantial infrastructures built to support PND may already be looking like a costly investment and drain on resources for a single application, even where a collaborative system is already in place. IT Directors are paying close attention to the cost of in-house services and are looking more and more at such collaboration to achieve cost savings wherever possible. In these circumstances, IAM technology plays a key role in enabling those forces access to one another’s resources and to realise the benefits of these exercises such as dynamic distribution lists and access to group resources. Identity management platforms may be hosted within either organisation, within a single environment controlled by mutual governance agreements, or in both organisations with federated services enabling cross-organisation identity management.

If your source identity information is not well organised, moving to an identity management platform of any configuration can be difficult. It is vital to prepare clean, reliable, and valid data. A solid, future‐proof Identity Management Platform (such as Microsoft FIM 2010) offers reduced administration, enhanced security, easier GRC reporting, and greater agility. It will also accelerate your goals, and as a bonus, it will also make you a more trustworthy federation partner, which as forces look to share services and combine IT budgets on multiple levels can be a very valuable added benefit.

Microsoft Partner guest post: Oxford Computer Group