.MSG File Format (Part 1)

In my previous two blog entries, I’ve focused on becoming familiar with the Compound File Binary Format which we discovered was similar to a FAT file system within a file. With that exercise behind us we’re ready to step up a level in the ecology of file formats. Analogous to ascending from chemistry to simple cell organisms, CFBF has given us the building blocks with which the great variety of application file formats are assembled.

Recently, I took the time to expand my view of application formats by investigating the workings of Outlook’s .msg format. Specifically, I was required to explain how a Rights Managed Email message could be dissected in order to read the contents hidden within. Having only a cursory knowledge of the Outlook message file format (.msg), and that being based of course, on CFBF, I needed only to discover where the critical components of the email message could be found. I will divide this blog into two parts. In part 1, I will overview the message file format described in MS-OXMSG in preparation for part 2. In part 2, I will describe in some detail, including code fragments how to find the compressed email attachment in a rights managed email and how it can be decompressed in order to read it plainly.

.MSG

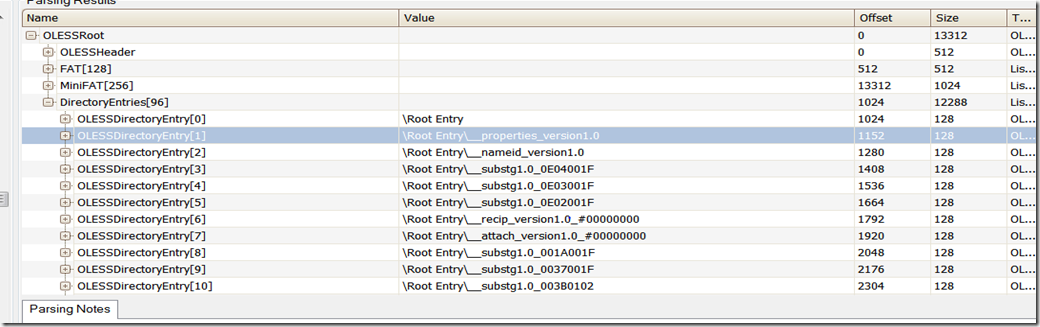

In this overview section, my goal is to describe the message store structure in a way that will enable you, the reader to recognize quickly the storages and streams in a sample .msg file and understand what you’re seeing. As always, to get the nitty-gritty detail of property names and fields sizes and the like, please refer to the actual documents that I’ll list as we navigate them.

A .msg file can be saved in Outlook or compatible email client and then viewed in an hex editor or binary file parser like OffViz or 010. MS-OXMSG tells us that a .msg file is a CFBF that contains storages and streams. However, imposed on the organic building blocks is a greater scheme. Message files contain objects which contain properties and collections of properties. For all intents and purposes, objects are represented by storages (CFBF), and properties are represented and reside in streams (also CFBF; remember that since a .msg file is a CFBF, *everything* must fall into a storage or stream.

Objects

Objects in a message store can be created by an email client (Outlook or compatible client) or the server (Exchange or compatible mail server). There are three basic types of objects you’ll find in a .msg storage structure. One is the email “object” represented by the .msg compound file itself. There is only one of these objects at the top level or root but there can be more email objects at lower levels, contained within the other two object types. The other two object types are the Recipient object and the Attachment object. The first, second and third Recipient objects have storages named:

__recip_version1.0_#00000000

__recip_version1.0_#00000001

__recip_version1.0_#00000002

The subsequent Recipient objects simply increment the serial number after the pound sign.

Likewise, for the Attachment objects, the storage naming scheme is the same:

__attach_version1.0_#00000000

__attach_version1.0_#00000001

Each of these objects (storages) has properties associated with it. This means that there are streams on each storage that contain information about the Attachment or Recipient in question. The format of these property streams is a little more complex and I’ll defer that for now.

There are actually two kinds of Attachment objects. There are embedded message attachments (which are other email messages that have been attached to this message) and there are “custom” attachments. In both cases, a substorage named __substg1.0_3701000D is created under the appropriate __attach_version1.0_#<serial number> storage for that attachment. What happens after that depends on the kind of attachment. For an embedded message attachment, the contents of the __substg1.0_3701000D storage will be yet another message, or in other words, what you would find if it was in its own .msg file. We could think of this recursively and define embedded message attachment storages to contain more messages.

On the other hand, a “custom” attachment is not another message, well, not necessarily. Once the __substg1.0_3701000D storage is created for a “custom” attachment, the email client or server creating this message store simply stops writing and hands the pointer to the __substg1.0_3701000D storage object (remember IStorage* ?) to another application. This other application could be Word, Excel, your favorite email client (that’s why I said, “not necessarily”) or any other application as long as it is capable of persisting it’s data to a compound file storage. That’s the beauty of Object Linking and Embedding. Outlook doesn’t care what’s in the __substg1.0_3701000D storage, it’s a custom data store.

So, now you know how to find the Recipient and Attachment object stores in a .msg file. But you should be thinking, “what about the properties?”. You’re right, the properties are what make each object more than just a hollow, empty shell.

Properties

Properties in the message file format as well as the Exchange and Outlook communication protocols, are defined in MS-OXPROPS. They define attributes of the object like the sender email, whether a read receipt was requested by the sender, whether this message was auto forwarded, an attachment’s filename, and the list goes on an on. Everything is described using properties.

Properties can be fixed or variable length and can also be multi-valued which are basically like arrays. Fixed length property types can be things like PtypInteger16 which is a 16 bit integer or PtypCurrency which is a 64 bit currency type. Variable length properties can be things like PtypString and PtypBinary which are strings and binary data, respectively. Multi-valued properties (arrays) come in two types, fixed and variable length. Fixed length multi-value properties are arrays with elements limited to certain fixed size types like the fixed length properties. Variable multi-value properties are arrays with elements limited to basically the same types as variable length properties. The most complex aspect of properties is most likely how they are stored in the message store.

Before explaining that, it’s important to reveal that there is a property stream at the highest level in the message store and one in each Recipient and Attachment object storage. This property stream, named “__properties_version1.0”, contains all the values or pointers to values for the properties of that object.

Fixed length properties are contained completely within the __properties_version1.0 stream. An entry for a fixed length property contains three pieces of information: a tag that uniquely identifies the property, a set of flags that tell whether the property is readable, writeable and/or must be present in this .msg file or attachment or recipient object, and an 8 byte field containing the value of the property (that’s the maximum length of a fixed property).

Variable properties are also contained in the __properties_version1.0 stream, however, because they are variable in length, only the tag, size and flags are in the __properties_version1.0 entries. By using the tag, the variable length property value can be located in a separate stream called “__substg1.0_<tag>”, where <tag> is the hexadecimal concatenation of the id and type for that property. See figure 1 below for an example showing the id and type hex values.

Multi-value properties work similarly. A multi-value fixed length property (array of fixed types) is stored identically to the way a variable length property is stored, only instead of each element of the array being say, a character as in a string, it’s some fixed type like a 64 bit integer.

Multi-value variable length properties actually require N+1 streams. N streams hold the values of the N elements and 1 stream holds the lengths of each of the individual elements. Each element’s value is of the same type but different length, for instance an array of strings. The length stream is named “__substg1.0_<tag>”, where <tag> again is the tag for the multi-valued variable length property being stored. The value streams are just derived serially from the length stream’s name: “__substg1.0_<tag>-00000000”, “__substg1.0_<tag>-00000001”, etc…

As an example to tie all this together, the PidTagSenderEmailAddress property is defined in MS-OXPROPS as:

2.1079 PidTagSenderEmailAddress

Canonical name: PidTagSenderEmailAddress

Property ID: 0x0C1F

Data type: PtypString, 0x001F

Figure 1: PidTagSenderEmailAddress definition from MS-OXPROPS

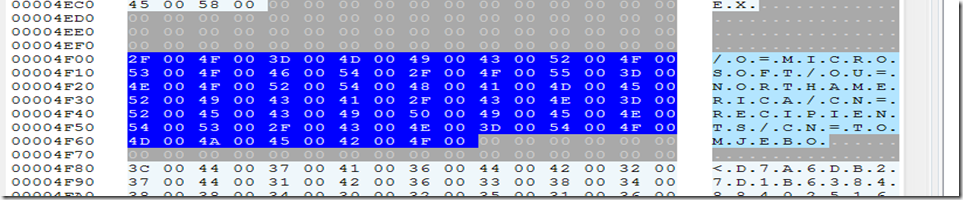

This tells us that the tag would be 0x0C1F001F (property id and data type), so this variable length property would be listed in the property stream (little endian format) as 1F001F0C for the tag. We can look for this in a sample .msg file:

Here’s the property stream for the whole message:

Figure 2: Properties stream

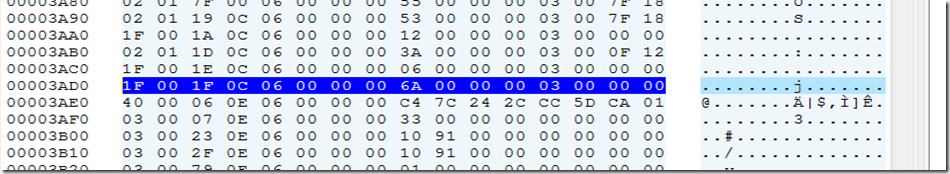

In that stream, we see the entry corresponding to the PidTagSenderEmailAddress property:

Figure 3: Entry in properties stream for PidTagSenderEmailAddress

According to section 2.4.2.2 of MS-OXMSG, the first four bytes are the tag (which we verify as the hexadecimal for PidTagSenderEmailAddress). The next four byte field contain the flags and the next four represent the count or length. In this case, length is 0x6A which is 106 decimal. Let’s look at the property stream and see the sender’s email address. The property stream is “__substg1.0_<tag>” which ends up being “__substg1.0_0C1F001F”.

Figure 4: Stream name for PidTagSenderEmailAddress property value

Found it! What are the contents of this stream?

Figure 5: String value for PidTagSenderEmailAddress

Well, “TOMJEBO”, that’s me!

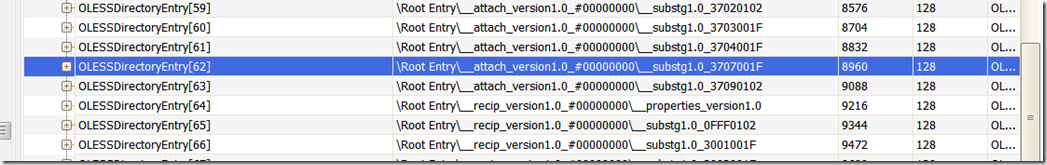

Remember that Attachment and Recipient objects have properties too. The example above shows the sender email address property of the base message itself. Let’s look at the Attachment object for this email message.

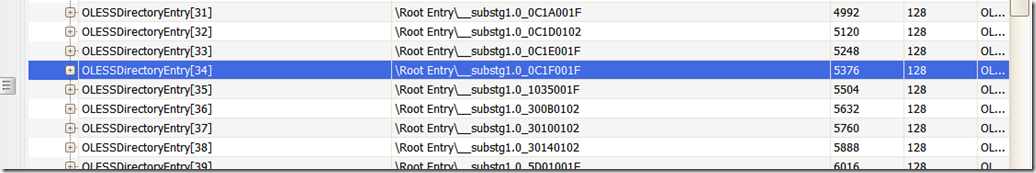

Figure 6: stream name for PidTagAttachLongFilename property of attachment object (00000000)

Note that the highlighted stream is “__substg1.0_3707001F” under the “__attach_version1.0_#00000000” storage. This tells us that this is the first attachment object in the message (by index 00000000) and that the stream represents the PidTagAttachLongFilename property of this attachment object. This should be the actual name of the file attached to the email message based on the tag (id and type) of 0x3707001F.

2.649 PidTagAttachLongFilename

Canonical name: PidTagAttachLongFilename

Property ID: 0x3707

Data type: PtypString, 0x001F

Figure 7: PidTagAttachLongFilename definition in MS-OXPROPS

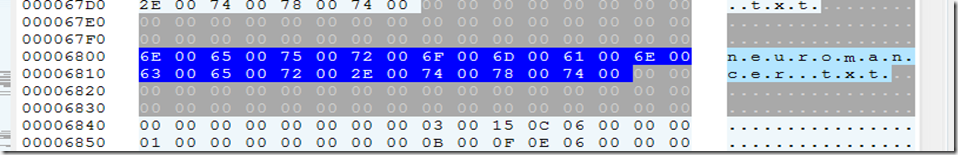

Figure 8: String value for PidTagAttachLongFilename property of the attachment object

And that is indeed the file I sent to my fellow Sci-Fi friends! This was also a string property and so to find the length, you would inspect the properties stream entry as we did in Figure 3 above.

One more note about properties. There is actually another kind of property called a named property. This is simply a property that is given a name and can be mapped to a property id or tag using the name. A message store contains yet another storage called the named property mapping storage. This storage is named “__nameid_version1.0”. Within this storage are three streams, the GUID stream “__substg1.0_00020102”, Entry stream “__substg1.0_00030102” and String stream “__substg1.0_00040102”. I won’t go into the details of this mechanism because it is more complex and we won’t need it in part 2 of this blog.

So at this point, you know that there are objects in message files and that they are described by their properties. You also have a working knowledge of the basic property types, how to find them and display their values. In part 2 of the blog, I will overview the rights managed email message format that builds upon this format and is described in MS-OXORMMS. I will also show how to use the publicly available ZLIB compression API’s for decompression of the contained email message.