How to Develop a Governance Program (that doesn’t suck the life out of your organization)

Enterprise Architecture has a role to play in both developing a vision of the future, and in providing governance and oversight to make sure that the organization can measure its progress towards that future.

The governance part is tricky. Architectural Governance is part of a larger fabric of governance that needs to exist throughout the organization, not just in IT but also in the business groups themselves. This means that governance has two masters. Governance has to align to business value, on one hand, and “measures of compliance” on the other.

For enterprise architecture, the business value lies on the proposition that systems designed with better architecture will be more flexible, maintainable, and reliable than systems that are not. Measures of compliance, on the other hand, can include things like “numbers of projects reviewed” or “evaluated quality of architecture is trending upward.”

In my opinion, governance is about motivating people to do the right thing. All compliance programs are really all about helping a person or team to do the right thing. There are may ways to that goal.

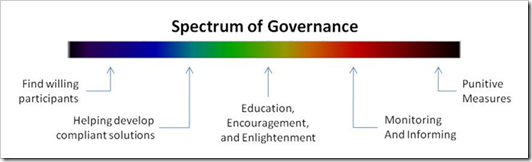

Of course, it’s a challenge, in any society or organization, to define what it means to “do the right thing.” I’ve noticed, as I conduct the architecture review program here in Microsoft IT, that there is a spectrum of governance. Different people in the organization tend to fall somewhere along this spectrum. Some folks want to “educate and encourage” good behavior, while others want to “monitor and inform” management about bad behavior.

The reason that I point out this obvious fact is that your Enterprise Architecture governance program will have many components. One component may surround innovation, and another may surround process improvement. In my organization, we have a governance process around architectural standards and review.

Each component will have an owner. The owner is the person who is accountable for insuring that a particular behavior (do the right thing) is happening. For architectural review in Microsoft IT, that is the Microsoft IT CTO Barry Briggs. He also happens to own the measurements for our architectural repository.

For each component of governance, it is important that you expose the governance owner to this spectrum and get agreement to the question: “Where on the spectrum do we want to be?” Even better: add the element of time to the conversation. “Where should we start?” and “Where should we end up?”

By getting your compliance owner to declare, specifically, where your compliance program needs to be on this spectrum, you are able to do many things:

- Everyone, including the compliance owner, knows and understands the posture that the compliance team needs to take. Other folks may want to interject their own opinion about where, in the spectrum, compliance should land. If the compliance program team members have a clear direction, then communication is clear, processes can be correctly designed, and expectations can be correctly set.

- The compliance owners’ direct manager (often an executive) can have some idea about where the compliance program is going and why it is going there. In some cases, this means that the executive can take responsibility for the level of risk they are accepting.

- Processes won’t get out of line with the intended behavior. I’ve seen examples, from our consulting engagements, where the business wants to encourage a particular behavior, and they asked for compliance processes, only to produce the opposite of the desired effect.

In one case, one of our partners was working with Microsoft on their SOA program. Their IT Leadership wanted to improve the use of shared services. They developed a shared service reuse program and a governance model to make sure that everyone used the services. The governance program was poorly rolled out and executed, and the program lost credibility.

As a result, whenever anyone asked about using those shared services, that person was derided and their idea discarded. In order to get past compliance, managers created a crafty way to “game the system” in reporting the results. While the compliance numbers looked good on paper, the actual use of shared services declined overall. The program that sought to increase the use of shared services caused it to decline instead.

Compliance is part of the game when you are trying to encourage good behavior in an organization. Making it work is not easy. The person responsible for insuring that compliance occurs has to have the right level of ownership and accountability. But just as importantly, they need to carefully consider where, on the spectrum of governance their program should be, now and in the future, in order to deliver on business value without encouraging different kinds of bad behavior.