New book: Successful Project Management: Applying Best Practices and Real-World Techniques with Microsoft Project

We’re excited to announce that Bonnie Biafore’s Successful Project Management: Applying Best Practices and Real-World Techniques with Microsoft Project (ISBN 9780735649804; 468 pages) is now available for purchase!

You can find the book’s Table on Contents and Introduction in this previous post.

In today’s post, please enjoy an excerpt from Chapter 1, “Meet Project Management.” A project has a set of objectives, a start and end, and a budget. The purpose of project management is to achieve the project objectives on time and within budget. In reality, project management is an ongoing task of balancing the scope against time, cost, quality, and any other constraints placed on the project. Read more to learn what a project is, the basics of managing one, and why project management is so important.

Meet Project Management

All white-collar work is project work.—Tom Peters

So you’ve been asked to manage a project. If you’re new to

project management, your first question is probably “What’s a project?”

No doubt it will be followed closely by “How do I manage one?” and

finally “How will I know if I did it right?” In this chapter, you’ll learn what

a project is, the basics of managing one, and why project management

is so important.

What Is a Project?

The good news is that you’ve probably already managed a project

without realizing it. You stumble across projects every day—at

work and at home. Besides the projects you work on at the office,

some of the honey-dos taped to the refrigerator door at home

are probably projects. The list on the following page shows some

examples of both business and personal projects.

■ Construct a suspension bridge

■ Landscape the backyard

■ Launch a new advertising campaign

■ Move into a new house

■ Discover a new drug and bring it to market

■ Build a retirement portfolio

■ Migrate corporate data to a new server farm

■ Throw your spouse a surprise fortieth birthday party

■ Produce a marketing brochure for new services

■ Obtain financial aid for your child’s college education

What is the common thread between these disparate endeavors? Here is one definition

of a project:

A project is a unique job with a specific goal, clear-cut starting and ending dates, and—in

most cases—a budget.

The following sections expand on each characteristic of a project so you’ll know how to

tell what is a project and what isn’t.

A Unique Endeavor

The most significant characteristic of a project is uniqueness. Frank Lloyd Wright’s design

for the Fallingwater house was a one-of-a-kind vision, linked to the land on which the

house was built and the water that flows past it. The design and construction of Fallingwater

was unmistakably a project.

Although every project is different, the differences can be subtle. Building a neighborhood

of tract houses, each with the same design and the same materials, might seem like

the same work over and over. But different construction teams, a record-breaking rainstorm,

or a flat lot versus a house built on a cliff transforms each identical house design

into a unique undertaking: a project.

Note Ongoing work that remains the same day after day is not a project. For

example, building walls and rafters for manufactured homes that you

ship to construction sites represents ongoing operations, which requires

a very different type of management. Assembling the components of a

manufactured home on site is a project.

A Specific Goal

Whether an organization launches a project to solve a problem, jump on an opportunity,

or fulfill an unmet need, it commits its time, money, and human resources to the project

to achieve a specific goal. This goal spawns the objectives the project must achieve and

also helps determine the project scope (the boundaries of what work is and is not a part

of the project).

Surprisingly, many projects aren’t set up with clearly defined goals, which is akin to a

herd of sheep without a Border collie. There’s lots of activity and angst, but very little

movement in the right (or even consistent) direction. That’s why one of your first tasks in

managing a project is determining what the project objectives are and making sure that

everyone involved agrees on them.

Clear-Cut Start and Finish Dates

Although some projects seem like they never end, a project has a clear-cut beginning

and a clear-cut end. The project goal helps delineate the start and finish of a project.

When the overarching goal is clear and the lower-level objectives are well defined, it’s

much easier to tell when the project is complete.

Within Budget

Projects aren’t supposed to last forever. Nor should they consume every available

resource like an organizational black hole. Every project has limited resources of some

kind, such as a price tag set by the customer, a limited number of available resources, the

number of work hours you can squeeze in between the start and finish dates, and so on.

As project manager, you must do your best to deliver the project within the various limits

you’ve been given. If you need more resources, you have to ask your management team

or the customer for permission.

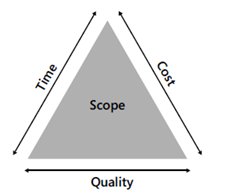

Something’s Gotta Give

The main constraints on a project—time, cost, and quality—are inextricably linked. This

set of constraints is so common that it’s known by several names, such as the project

triangle, the scope triangle, and the triple constraint. Figure 1-1 shows one interpretation

of the project triangle.

Figure 1-1 For a given scope, you can choose the values for two of the three constraints (time, cost, and

quality), which then determine the value of the third.

If you change any of these constraints, something else has to give. In other words, if

you’re building a house, you can build a good house quickly, but it’ll cost you plenty. On

the other hand, you could build a house quickly and cheaply, but it won’t be very good.

In reality, project constraints are more than a triangle because you can juggle other factors,

too. For example, if the customer won’t budge on time, cost, or quality, you can look

at changing the scope of the project, such as building a smaller house or one with fewer

time-saving features. Resources are often a constraint. Although everyone might agree

on scope, time, cost, and quality, a resource shortage could require a longer schedule or

a higher price to bring on additional hands.

The good news is that you can balance project constraints in any number of ways. That’s

one of your tasks as a project manager, as you’ll learn in the next section.

What Is Project Management?

Projects happen whether they’re managed or not. Left unattended, projects seem endless,

expend all available resources, and yet still don’t deliver what they’re supposed to.

Some folks assigned to manage projects take great liberties with the guiding statement

“Do whatever it takes.” They get the project done, but they leave behind a path of destruction

and dazed, exhausted workers. So, what is project management and how does

it help achieve success?

Regardless of the shape and size of your project, project management boils down to

answering the following questions:

■ What problem are you solving? Dr. Joseph M. Juran, a project management

consultant well known for his work on quality and quality management, defined

a project as a problem scheduled for solution. One of the first steps in successful

project management is correctly identifying the problem that the project is supposed

to solve. As you learn in Chapter 2, most people jump straight to solutions

instead of defining the problem. For example, “We need a deck in the backyard” is

a solution for a landscaping project. Unless you know what the underlying problem

is, you can’t tell whether it’s the right solution.

Note Sometimes, problems come in the form of opportunities of which

you can take advantage. For example, you might undertake a

project to solve a problem of high rates of product returns. Or you

might launch a project to enhance a product to increase market

share.

Behind even the simplest problem statement is a boatload of detail about the

work to be done. What objectives must the project achieve? Are there specific

requirements the customer has in mind? What work has to be done to achieve the

objectives and satisfy the requirements? Depending on the details, the backyard

landscaping work could be to install a deck; install a patio; or, if low-maintenance

is the main objective, pave over the yard.

■ How are you going to solve it? You don’t just let a team of carpenters loose

in the backyard with lumber and nails and say, “Go build a deck.” You have to

develop a plan for getting the project done, including defining each task in detail,

identifying the resources you need, determining how much they cost, and defining

how long the work will take.

■ How will you know when you’re done? If a project’s objectives and requirements

are well defined, it’s easy to tell when you’re done. If the objective of your

project is to reduce product returns by 30 percent, you can count the number of

returns and calculate the percentage improvement. With some projects, success

isn’t so clear-cut. Either way, you have to define success criteria up front in such a

way that it’s obvious whether or not you succeeded.

■ How well did it go? One sign that a project went well is when the customer

signs off on the project and writes the final check for payment. You also have to

evaluate how well the entire process went. Capturing lessons learned is an important

but often ignored step at the end of a project. The project team meets to

document what went well, what did not go well, the reasons for success or failure,

and what could be done differently the next time a similar project comes up.

With those insights, you can find ways to improve how you manage projects and

achieve success more easily on future projects.

Project Management Processes

A project has a set of objectives, a start and end, and a budget. The purpose of project

management is to achieve the project objectives on time and within budget. In reality,

project management is an ongoing task of balancing the scope against time, cost, quality,

and any other constraints placed on the project. According to the Project Management

Institute’s Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge, project management

is divided into five process groups:

■ Initiating Initiating is officially committing to start a project. The anointed

project manager unearths the real objectives of the project, identifies the potential

project stakeholders, and works with the customer and other stakeholders

to come up with an approach to achieve those objectives. In effect, the initiating

phase answers the question, “What problem are you solving?” The project manager

prepares a summary of the project and its business benefits. The initiating

phase is complete when management gives approval to move to the planning

phase.

■ Planning Planning is working out the details of how you are going to solve the

problem. During the planning phase, you identify all the work that must be done,

who does it, when they do it, how long it takes, and how much it costs. With skill

and some luck, the project achieves its objectives within the desired time frame

and budget, producing results at the desired level of quality and without turning

the assigned resources into burnt toast. Planning isn’t complete without identifying

the risks that could interfere with success and how to respond to them.

Planning up front pays off many times over during the execution of a project. You

can either spend time planning early on or spend far more time putting out fires

later.

Tip With the popularity of project management programs such as

Microsoft Project, many people mistakenly consider scheduling a

project to be the same as managing a project. They think of the

schedule as the complete plan for the project. When you understand

what project management really is, you can learn how to

apply the features of Project to manage projects more effectively.

Executing Executing a project is a project manager’s ongoing work for the life

of the project. The first step is launching the project. You get the project team

on board and explain the rules. After that, you keep the project team focused on

doing the right things at the right time—as outlined in the project plan.

Controlling Controlling a project is also ongoing work, but it focuses on monitoring

and measuring project performance to see whether the project is on track

with its plan. As the inevitable changes, issues, surprises, and occasional disasters

arise, the project manager can determine the kind and magnitude of course correction

that is required to get the project back on track.

Closing Closing includes officially accepting the project as complete, documenting

the final performance and lessons learned, closing any contracts, and releasing

the resources to work on other endeavors. Are the success criteria satisfied?

Does everyone involved agree that the project is a success, and have they officially

signed off on acceptance?

Best Practices

At its best, project management is as much art as science. Getting to the true objectives

and requirements can be tough enough. Then you must mix scope, time,

cost, quality, resources, and other constraints in the right proportions to achieve

those objectives. For example, if quality is the key to differentiating a product

from the competition, a longer schedule and higher budget might be the preferred

choice. If getting that same product to market before the competition is

critical, reducing the product features (scope), increasing the size of your team, or

accepting a slightly higher level of errors (reducing quality) might be better.

As project manager, you can’t change constraints such as time, cost, or the resources

assigned. However, you can control how you use them. If you can make

your plan work without affecting anything or anyone outside of your project

team, you can push on without having to ask for anyone’s permission.

If you can’t make your plan work, you can seek permission to change one or

more of your project’s constraints. For example, you can go to the management

team with hat in hand, asking for more resources to shorten the schedule. As

a last resort, you can appeal to the customer for more time, more money, or a

reduction in scope.