Keeping watch in the night

The following blog post was guest authored by Ana Isabel Zorrilla, project manager at EIC BBK-Dravet Syndrome Foundation, a Spanish nonprofit organization dedicated to the treatment and cure of Dravet syndrome and related disorders.

Imagine what it’s like to go for weeks on end without a decent night’s sleep. For Julian Isla of Madrid, Spain, this scenario requires no imagining. He has lived it, spending night after sleepless night lying awake, listening for the telltale signs that his child is having a seizure. You see, Julian’s son, Sergio, suffers from Dravet syndrome, a severe form of epilepsy. Children with Dravet syndrome experience frequent seizures; from an average of one crisis per week in the mildest cases, to one or more a day—or even multiple seizures per hour—in the most severe instances. These attacks occur more frequently while a child sleeps, so parents often struggle to stay awake seven nights a week, prepared to give their child emergency medical treatment in the event of a prolonged seizure.

When he was born, Sergio was a healthy baby. The seizures began when he was four months old, and he was diagnosed as having Dravet syndrome after experiencing several long-lasting seizures and multiple admissions to the pediatric intensive care unit. After receiving his son’s diagnosis five years ago, Julian connected with other Dravet families, and together they explored the idea of creating an organization to promote research on the condition. They got in touch with the Dravet Syndrome Foundation (DSF) in the United States, and out of that connection, the Spanish Delegation of the DSF was born. Julian serves as the executive chairman of the Spanish Delegation, which has nine employees, including me. Our organization is involved in multiple research projects, including a search for new drugs that can treat Dravet syndrome.

Technology has been pivotal for our group; this year, for example, we conducted the world’s first genetic tests for Dravet syndrome, using state-of-the-art technologies. Today, children with Dravet syndrome are being diagnosed by a new generation of genetic tests running on Microsoft Azure that the Spanish Delegation pioneered. Our group’s technological bent is hardly surprising given Julian’s background: with a degree in computer science and some 20 years of professional experience in the IT sector, he currently works for Microsoft in Madrid, where he manages a team of software consultants.

As soon as Julian heard about Kinect for Windows, he began exploring the use of the technology to help Dravet families. He was aware of the technology’s potential for medical applications, thanks to interactions with colleagues in the Microsoft Madrid offices. About the same time, the Spanish Delegation created EIC BBK, a development center focused on e-health applications. Julian proposed that the center investigate the use of Kinect for Windows to monitor Dravet children while they slept. With the Kinect sensor serving as a sentinel, Julian thought the beleaguered parents might get some much needed sleep themselves.

The use of monitors to detect seizures is not groundbreaking: there have been multiple studies and projects on seizure monitor systems. What is new and exciting is the Kinect sensor’s exquisite sensitivity, the result of its multisensory inputs. “With a color camera, an infrared detector, and an array of microphones, the Kinect sensor can detect physical movement and acoustical changes with tremendous accuracy,” says Julian. He adds, “The affordability of the Kinect sensor is another huge advantage.”

By the end of 2013, EIC BBK had started the “Night Seizure Monitor” project, a research initiative that uses Kinect for Windows. This project’s aim is to track the child’s movements while sleeping. When the Kinect sensor detects movements that follow a seizure pattern, an alarm warns parents that their child might be having a seizure. This solution provides dual benefits: when a seizure is detected, the monitor system ensures that the child gets medication right away to reduce the length and intensity of the episode. And when no seizures occur, the monitor enhances family’s quality of life, because parents are able to enjoy a restful sleep.

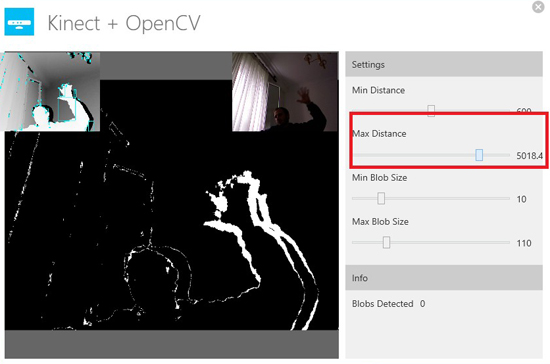

At the outset, developers programmed the Kinect sensor to be able to detect the movements of a child even if he or she was in a darkened room and lying under a blanket or comforter, above. Then, they added the ability to spot seizures that begin with abrupt movements or loud vocalizations, below.

Using data collected by its color camera and depth sensor, Kinect for Windows detects seizures by comparing changes in the child’s body position between two sequential frames. If these changes are frequent, the seizure alarm sounds. In addition, the sensor’s microphone plays a role in recognizing the seizures, as the system has been programmed to respond to the shouts that typically accompany the onset of a Dravet seizure. The Kinect-based solution can process this sound and calculate the child’s location in the room.

As participants in the Kinect for Windows Developer Preview program, our developers here at EIC BBK have been testing a preview version of the Kinect for Windows v2 sensor and SDK since December 2013, exploring the technology’s potential to improve upon the existing Night Seizure Monitor research. They are especially pleased with the v2 sensor’s infrared capabilities—which provide an even higher quality image—and its wider field of vision and greater depth range. These enhanced features should make the Night Seizure Monitor even more valuable.

Moreover, the developers are eagerly awaiting the general availability of the Kinect for Windows v2 sensor and SDK, which promise enhanced discrimination of facial expressions. The developers believe the enhanced face tracking capability will help the monitor detect those seizures that do not present limb shaking but rather are manifested by movements of the eyes and mouth.

The Night Seizure Monitor initiative is a great example of how needs can promote creativity. Julian had a problem at home, and rather than accepting it as unavoidable, he decided to seek out a solution.

It also shows the power of teamwork: Julian has received enormous support from colleagues at Microsoft; right now a dozen of them are helping our organization as volunteers.

Finally, it demonstrates how technology can empower people. Julian sums up the experience eloquently, observing that “When you have a child with special needs, everything seems filled with problems. You feel impotent. I’ve had the privilege of using technology for a project that will, we believe, improve the lives of many young patients and provide a sense of control to their families. I feel proud to work for a company whose technology can make such a difference in people’s lives.”

While the Night Seizure Monitor is still a development project, we hope to have a fully functional prototype available for testing with Dravet Foundation families by the end of 2014. After that, our goal is to make the monitor available to Dravet families around the world. But as wonderful as this development will be, it is but a way station in the Dravet Syndrome Foundation’s ultimate mission: to find a cure for this disorder. Despite the difficulty of this quest, DSF supporters, volunteers, and workers are laboring tirelessly to achieve it. We call it our “moonshot,” taking inspiration from US President John Kennedy’s audacious mission to send a manned mission to the moon. Our moonshot represents the dream of parents who will never give up.

Ana Isabel Zorrilla, project manager,

EIC-BBK– Dravet Syndrome Foundation

Key links