Structuring Visual Studio Solutions

Over the years, I have refined how I create Visual Studio projects based on lessons learned and new capabilities provided with each subsequent release of Visual Studio.

When starting a new project from scratch, I start by creating a blank Visual Studio solution. [This "clean slate" scenario doesn't happen very often, but I can easily think of five different occasions since I joined Microsoft.] If you choose to go straight to creating an actual project, for example a C# Class Library project, the first release of Visual Studio .NET (which seems like eons ago) would automatically create the solution with the same name as the project and, if I remember correctly, it would drop the .sln file in the same folder as the .csproj file. Note that Visual Studio 2005 allows you to specify a different solution file as well as the location. However, you know the old saying about "old dogs and new tricks."

I recommend a naming convention that utilizes the company name and the project (or product) name -- the latter usually being some code name since the marketing folks won't typically be involved for several months to come.

For the purposes of this blog post, I'll use Microsoft.Samples.

Now that we have a solution name, we need a place to create the solution. How about C:\NotBackedUp\Microsoft\Samples\Main? Okay, that seems fairly straightforward, although the NotBackedUp part seems a little quirky. (You can read my other post if you really care to understand this moniker.)

Oh yeah, and where did Main come from?

That was something I neglected to include until recently (or rather not something I would think about until much later in the project). It's all about branching, or more specifically, planning ahead for branching. There are some great references out there on effective (and inffective) branching models. One of the best that I remember reading is The Importance of Branching Models in SCM (and to be honest, I must have read it 2-3 times before I really understood it). The gyst of it is that if you plan ahead, supporting multiple versions (with parallel development) is actually fairly easy, even with a "low-end" configuration management tool such as Visual SourceSafe. [No offense intended to the VSS team; actually we end up using VSS on almost all of the projects that I work on due to the team size. Let's face it, TFS is obviously much more powerful than VSS but it also requires a lot more "infrastructure" to setup and maintain.]

So, the whole point of initially putting the solution in the Main folder from the start, is that we are explicitly creating our main development branch from the get-go. In other words, all of the primary development occurs on the "trunk", and at appropriate times, we'll create branches as necessary (for example, to stabilize for a v1.0 release).

So, if you know your way around Visual Studio even just a little, you should be able to quickly create the following shell structure:

Figure 1: Solution Explorer view of Visual Studio solution

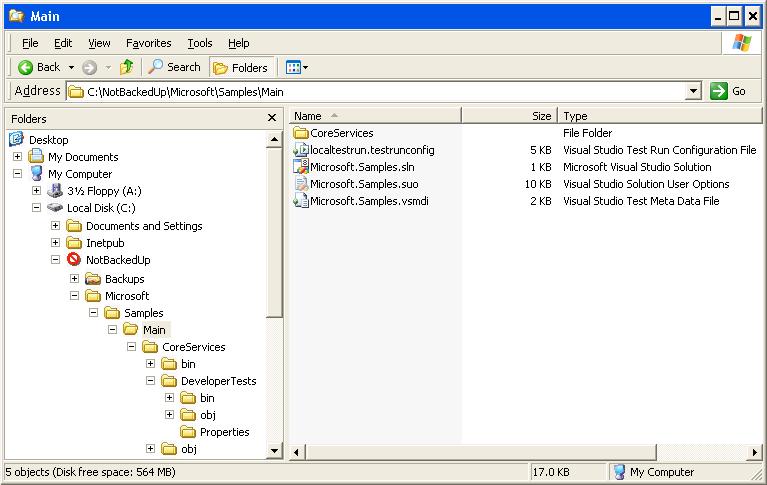

In Windows Explorer, the corresponding folder structure looks like this:

Figure 2: Windows Explorer view of Visual Studio solution

A few notes...

- I like to use solution folders to "partition" the solution into manageable chunks. I'm a huge fan of the "single/master" solution approach. However as the solution grows larger I need way to quickly unload the majority of the projects so that we can quickly build and debug just the specific features I happen to be working on at the particular moment. I've worked on several projects where customers already had multiple solution files in place, and the effort required to compile the entire code base goes up dramatically compared to using a single solution. There are valid reasons for creating multiple solutions, the most obvious being enterprise level frameworks and utilities that are shared across multiple projects. As long as these are fairly "baked" and seldomly change, then building (and referencing) them separately (i.e.using file references instead of project references) is not an issue.

- You typically have a set of classes that contain low-level "helper" methods used by many of the other projects in your solution. The CoreServices project gives you a place to put these. The important thing about CoreServices is that is does not reference any other projects within that solution. [I didn't make up the name "CoreServices" -- if memory serves, I "stole" this from Jim Newkirk after browsing through the source code for NUnit a few years ago.]

- The CoreServices.DeveloperTests project contains all of the unit tests (created by the Development team) for the CoreServices project. While we could certainly choose to leave the project in the default CoreServices.DeveloperTests folder created by Visual Studio (i.e. C:\NotBackedUp\Microsoft\Samples\Main\CoreServices.DeveloperTests), it only takes about 30 seconds to remove the project, rename the folder from CoreServices.DeveloperTests to just DeveloperTests and then add the file again. The short reason is that I really hate to see "dots" in folder names, because where do we draw the line? If you don't do this, then pretty soon you start seeing 30 project folders within a single folder.