Script Polyglots

Lately, there’s been a resurgence of interest in hiding script inside files of other types; sometimes this is known as a polyglot file. On Twitter, there’s been some excitement about a new tool that creates GIF/JavaScript polyglots.

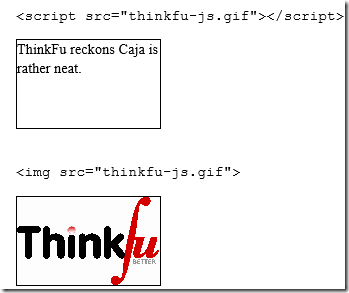

As you can see in the example provided in the aforementioned blog, when referenced as the source of a script element, the script runs, and when referenced as the source of an img element, the GIF image renders:

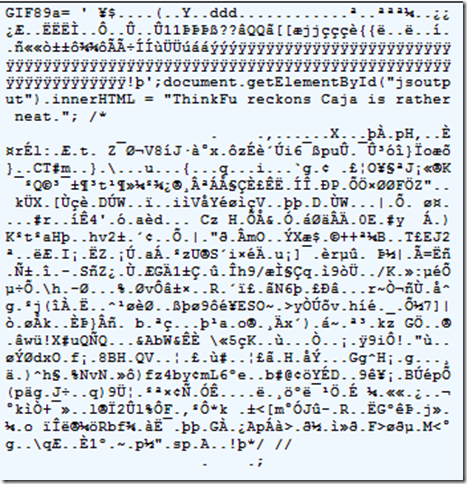

Neat. But the secret is quickly revealed if we peek at the raw bytes:

As you can see, this image starts with the standard GIF89a signature. Then, the cleverly-crafted file takes advantage of the fact that the subsequent bytes encode the size of the image. The creator specifies that the image shall be 8,253 pixels wide by 8231 tall, which is encoded using the hexadecimal values 0x203d 0x2027, which are encoded in GIFs as 3d20 and 2720 with the least significant byte first.

When interpreted by the JavaScript parser, these four bytes are interpreted as an equals sign, space, single quote, space. This, in turn, causes a JavaScript parser to read the file as a variable declaration, followed by more JavaScript statements, and ending with a long garbage comment.

So, why is this interesting? Is it a horrible security hole?

No, not really.

Back before IE8, IE would eagerly seek out HTML even inside files served as images, and as a consequence, websites that accepted user-supplied images and served those images were at risk because any HTML documents “sniffed” from the files would be running in the security context of the victim site. IE8 changed things such that HTML would never be sniffed from files delivered with an image/ MIME type.

MIME-Sniffing HTML from images was much more dangerous than sniffing script, because script runs in the context of the hosting page, not in the context of the server that delivers the image/script. So, in order for something bad to happen today, a victim site must not only allow polyglot files to be uploaded, but also it must allow an attacker to inject a <SCRIPT SRC> tag into the markup that the site serves. In most cases, this is not very practical/interesting (especially because any such injection probably would be an XSS in and of itself).

Nevertheless, there’s still a bit of interest here because polyglot files could conceivably be used as an attack against Content Security Policy. Consider a CSP-protected site that decides to allow visitors to specify any SCRIPT SRC they like, relying on CSP to ensure that the SRC attribute points to a “safe” server. Also, our victim site must allow image uploads to a path under the CSP-specified script-src. With a polyglot file, the server is conceivably at risk, despite CSP.

There are a few best practices that help protect against attacks like this:

- Don’t ever serve user-submitted content from your application’s domain. If your application runs on example.com, serve user-submitted content from example-usercontent.com.

- When specifying a CSP script-src directive, ensure that it specifies a location where only known and trusted scripts reside.

- Consider resaving (and optimizing) user-submitted image files. Reencoding image files can improve performance, privacy (dropping GPS coordinates, etc), and security (by breaking polyglots).

- When serving user-submitted image files, serve them with the X-Content-Type-Options: nosniff response header.

The last item bears some explanation. Back in IE9, the MIME-Sniffing logic was improved such that a SCRIPT element whose response bore the nosniff directive would be rejected if the MIME type does not match one of the following values ["text/javascript", "application/javascript", "text/ecmascript", "application/ecmascript", "text/x-javascript", "application/x-javascript", "text/jscript", "text/vbscript", "text/vbs"]. This protection was added to help protect against other types of attacks (specifically, the leaking of cross-origin information in JavaScript error objects) but it’s useful here as well.

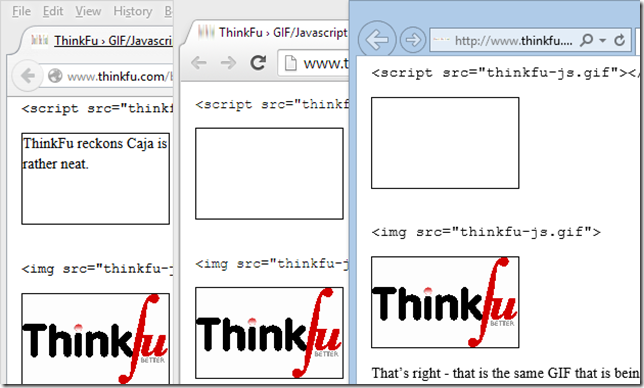

We can add this response header using Fiddler's Filters tab to prototype the effect. As you can see below, Chrome 39 also supports the nosniff directive, but Firefox 36 does not:

As far-fetched as the attack scenario may be, it still may make sense for browser vendors to require a proper MIME type on any SCRIPT response when CSP is in use. They might even want to broaden the existing logic such that image/ responses can never be used as anything other than an image.

-Eric Lawrence

MVP, Internet Explorer