Shadowcasting in C#, Part Three

Before we get started, thanks for all the great comments to the previous couple of posts. I'll be updating the algorithm to try to make even better-looking circles of light based on the comments. Like I said, there's a lot of subtleties to these algorithms and I am just learning about them myself.

To that end, in today's episode I am going to spend the entire prolix article analyzing a single division operation. You have been warned.

Before we begin though, some jargon. A cell which is invisible that by our physical interpretation ought to be visible, or a cell which is visible that ought to be invisible we will call an "artifact". An "artifact" is the product of our algorithm (or some detail of its implementation) not being a sufficiently accurate model of real-world physics. Today's article will be all about artifacts.

The actual workhorse that implements the field-of-view algorithm is this method that we mentioned last time:

private static void ComputeFoVForColumnPortion(

int x,

DirectionVector topVector,

DirectionVector bottomVector,

Func<int, int, bool> isOpaque,

Action<int, int> setFieldOfView,

int radius,

Queue<ColumnPortion> queue)

{

This method has two main purposes. First, it assumes that all points in the portion of column x bounded by the top and bottom vectors are in the field of view, and marks them accordingly; some of them might be outside the radius, but the rest of them are by assumption visible from the origin. Second, it determines which portions of column x+1 are in the field of view and adds them to the work queue for later processing.

We described the algorithm as working from top to bottom of the portion of the column under consideration. Therefore the very first question we must answer is "which exactly is the top cell in the column portion, given the column number and the top direction vector?"

If the center point of a cell in column x happens to fall exactly on the top direction vector then it is pretty clear which is the top cell. Suppose for the sake of argument that's the case. The top cell is then computed by x * topVector.Y / topVector.X. This division is exact. Proving that is an easy bit of algebra and is left as an exercise.

So perhaps we should say that even if the division is inexact, we compute the top cell by:

int topY = x * topVector.Y / topVector.X;

(Note that we'll assume throughout that the numbers we are multiplying and dividing are small compared to the range of int, and therefore do not overflow.)

What happens if the division is inexact? We know that in C# an inexact integer division always rounds towards zero; it rounds down if necessary.

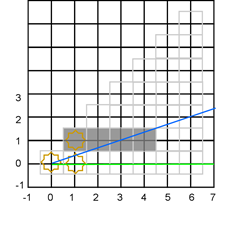

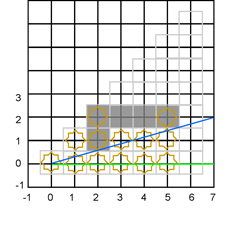

Rounding down is a bad idea because it doesn't model the physical world well and makes for extraordinarily bad-looking gameplay. Consider this extremely common scenario:

After processing column one we lower the slope of the top direction vector to one-third. Is point (2,1) in the field of view? It sure seems light it ought to be since its entire bottom surface is within the field of view. But if we do 2 * 1 / 3 we get zero, so no, the top cell that is visible in this column is (2, 0). We mark that as visible and continue on to column three without changing the slope. The top direction vector now intersects the center of cell (3, 1), so it and (3, 0) are visible. We lower the slope of the top vector to one-seventh, and now cell (4, 1) is not visible, again because we are rounding down. After processing all the columns shown here the state of affairs would be:

This matches neither the desired physics nor the desired gameplay; a straight corridor should not have weird "gap" artifacts. Notice also that the resulting top vector is a little bit too steep; we never considered the opaque cell in column four to be possibly shadowing anything beyond it; the rest of the world is only in the shadow of cell (3,1), not (4,1). Rounding down is clearly unacceptable.

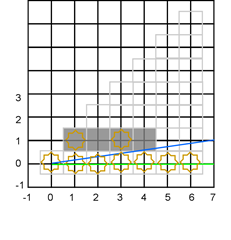

Well. What to do, if rounding down doesn't work? Maybe we should round up!

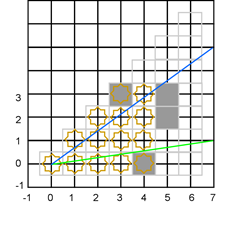

That solves the problem for long corridors; now what happens is cell (2,1) is determined to be visible by rounding up, so the top slope is lowered to one-fifth. Then cell (3, 1) is determined to be visible, so the slope is lowered to one-seventh. Then cell (4,1) is determined to be visible, and the slope is lowered to one-ninth. That seems to be much better.

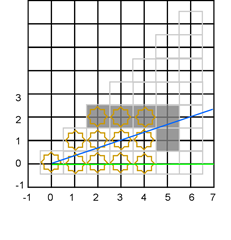

Moreover, we now also have the nice property that the corners of a room are visible. Consider this common situation:

Cell (5,2) will be visible, which will render nicely, particularly if "box drawing" characters are used to represent interior corners as is the case in many roguelike games. This is a desirable artifact.

But surely now we have the opposite problem; if we round up then we are potentially making cells visible that ought to be in the shadow of some opaque cell. Let's take a look at an example of that.

Cells (3,2) and (4,2) are unambiguously in the shadow of cell (2,1). But look carefully at column five. Even though the top vector does not pass through any part of (5,2) it does pass slightly above point (5,1) and therefore the division will round up such that (5,2) is considered visible! With this rounding algorithm you can "peek around a corner" a little bit. Visible point (5,2) is an artifact.

Even worse, consider what happens when the algorithm discovers that there is an opaque-to-transparent transition between (5,2) and (5,1). The top vector will be moved up!

That top vector is now steeper than it used to be. (Also note that if this had been the top vector when processing column four then the point (4,2) ought to have been visible.)

Obviously this situation can continue; rounding errors in later columns can continue to make the top vector steeper and steeper. (Exercise for the reader: is there a maximum slope that the top vector can attain via repeated applications of rounding error?)

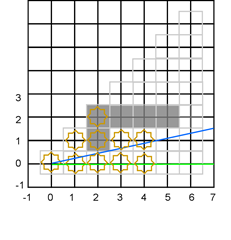

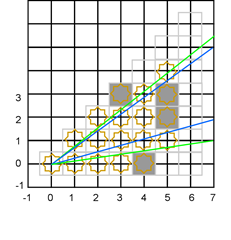

We could easily put a check into the algorithm implementation to say that the top direction vector must never go from a shallower slope to a steeper slope. If we decided to use always-round-up rounding then we might do that. But it gets worse. Consider this scenario that I mentioned last time:

Last time I made the simplifying assumption that cell (5,4) was out of range, and therefore not visible. But suppose the radius is larger; let's analyze this one in more detail. We'll round up to determine the highest visible cell in the column portion bounded by these vectors, so cell (5,4) is visible. We then find transitions from visible (5,4) to opaque (5,3) and opaque (5,2) to visible (5,1) (assuming that (5,1) is the bottom cell of the range; we'll discuss that assumption next time.) Therefore we have to divide this up into two sub-portions for column six. To compute the upper portion we keep the top vector the same and move the bottom vector up; to compute the lower portion we keep the bottom vector the same and move the top vector down. The result is this godawful mess:

The top direction vector of the upper column portion is now below the bottom vector. Yikes!

This error again allows the player to "look around corners" in a weird way, but it really is not so bad. What will happen here is that as long as the mis-ordered vectors identify the same cell as the top and bottom cell of the visible portion for a particular column, that single cell will be visible. As soon as the portion is large enough that the top and bottom cells are different, the loop that goes from top to bottom will immediately exit.

Again, we could prevent this situation by doing a check that verifies that the bottom vector is never moved to be above the top vector. However, perhaps we'd decide that this situation is sufficiently rare, and the artifact is sufficiently benign, that we'd just allow it.

Rounding up seems better than rounding down, but this still isn't great. Hmm. What if we rounded to the nearest lattice point?

Scenario One is unchanged. We still correctly compute visibility of the entire long straight wall.

Scenario Two is unchanged. We still make the desirable "corner artifact".

Scenario Three is improved. Cell (5,2) is not treated as visible, which is good because it is entirely in shadow. The top vector is not made more steep.

Scenario Four is unchanged. We can still end up in a situation where the top and bottom direction vectors are mis-ordered.

That's no change in three scenarios and a great improvement in one, so this is an unambiguous win, right?

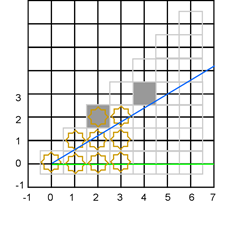

Not quite. Consider this scenario:

If we round to nearest then (4,3) is not visible, even though a full 30% of its lower surface has line of sight from the origin. Furthermore, by not treating this cell as visible, we fail to lower the slope of the top vector from 3/5 to 5/9, possibly allowing more cells to be visible in higher columns that ought to be shadowed by (4,3). Round-up would have treated (4,3) as the topmost cell in the region, so round-to-nearest is not an unambiguous win over round-up.

At this point it would be wise to take a step back and ask ourselves if continuing to tweak how the division rounds is the right thing to do. When you propose three different plausible calculations and they all turn out to be wrong in different ways, there might be an invalid assumption somewhere in the mix.

The invalid assumption is that y = SomeKindOfRoundingOf(x, top.Y, top.X) is correct in the first place. It is not. This calculation, no matter how you round it, is fundamentally calculating where the vector intersects the center of the column. Why is the center of the column at all relevant? It is the edges of the cell that cast shadows!

What we want to compute is "what is the highest cell in the given column that is anywhere intersected by the top direction vector?" The slope of the top direction vector is always positive; the line is always "sloping up", so the top cell can be identified by figuring out where the vector leaves the column. What we should be doing is working out the intercept of the vector with x + 0.5, not with x.

How are we going to do that? The first thing to observe is that (x + 0.5 ) * top.Y / top.X is the same thing as (2 * x + 1) * top.Y / (2 * top.X). Now everything is in integers. Let's work out the quotient and the remainder in integers:

int quotient = ((2 * x + 1) * top.Y) / (2 * top.X);

int remainder = ((2 * x + 1) * top.Y) % (2 * top.X);

Let's look at a bunch of possible different possibilities. Suppose the direction vector is (5, 3), so we go five "right" for every three "up". The interesting points are the points where the vector exits the column on the right hand side. The quotient is the black horizontal line below the interesting point. In this example the remainder is the number of tenths the interesting point is above the quotient line. (Tenths because the denominator is 5 x 2.) The numbers at the bottom of each column are the remainders:

(Note that the dividend will always be an odd number and the divisor will always be an even number, and therefore the remainder will always be an odd number. Proving those assertions is left as an exercise. Hint: what possible y values can the top direction vector take on if restricted only to integers?)

So, how should we round? Consider the columns labeled 1 and 3. In those the rounded-down quotient correctly identifies the cell that the direction vector intersects. The columns labeled 7 and 9, however, have a problem; the quotient is one below the correct result; we have rounded down incorrectly. What about the column labeled 5? If the remainder is exactly the "run" value of the top direction vector then the vector passes exactly through the boundary where two cells meet; which one should be visible? Since this is the "top" bounding vector, we should round down; no area of the upper cell is visible.

So, in summary: use the rounded-down quotient as the top cell in the column if the remainder is top.X or less; otherwise, round it up by adding one to the quotient.

Does that solve our problems?

Scenario One: Good. We correctly put the whole corridor wall into the field of view.

Scenario Two: Good. We "correctly" put the invisible corner cell into the field of view.

Scenario Three: Good. Cell (5,2) is not identified as being visible, and therefore the top vector's slope is not increased.

Scenario Four: Bad. We incorrectly identify cell (5,4) as being visible through cell (5,3), and thereby produce not only an artifact, but an "inverted" set of top and bottom vectors for the next column.

Scenario Five: Good. We make cell (4,3) visible and lower the slope of the top vector accordingly.

This algorithm is not perfect; we still make some artifacts. How might we solve the issue of scenario four?

A couple ways come to mind. One is that we could check to see if the direction vector enters the column at (5,3) and exits at (5,4). If it does then (5,4) is only the top cell if (5,3) is transparent.

Another way would be to allow cell (5,4) to be visible regardless -- this might have nice properties for showing corners, even if the cell is technically an artifact -- but to detect whether the new bottom vector is steeper than the old top vector and not allow the recursion.

In my actual implementation of last week I decided that solving the problem of scenario four is not worth it to me; I allow the artifacts and the inverted range. The results seem pretty decent.

As I warned you, it took me an extremely long article with nine complicated diagrams to figure out how to divide two numbers to determine the top cell. I said this was going to be excessively detailed!

Next time we'll do the same analysis for determining the bottom cell in the column portion. Hopefully things will go a bit quicker now that we have the basic idea of how rounding produces artifacts down pat.