Building Highly Scalable Java Applications on Windows Azure (JavaOne 2010)

JavaOne has always been one of my favorite technology conferences, and this year I had the privilege to present a session there. Given my background in Java, previous employment at Sun Microsystems, and the work I’m currently doing with Windows Azure at Microsoft, it’s only natural to try to piece them together and find more ways to use them. Well, honestly, this also gives me an excuse to attend the conference, plus the co-located Oracle OpenWorld, along with 41,000 other attendees. ;)

JavaOne has always been one of my favorite technology conferences, and this year I had the privilege to present a session there. Given my background in Java, previous employment at Sun Microsystems, and the work I’m currently doing with Windows Azure at Microsoft, it’s only natural to try to piece them together and find more ways to use them. Well, honestly, this also gives me an excuse to attend the conference, plus the co-located Oracle OpenWorld, along with 41,000 other attendees. ;)

Building Highly Scalable Java Applications on Windows Azure - JavaOne S313978

View on Docs.com https://docs.com/8FAZ.

A related article published on InfoQ may also provide some context around this presentation. https://www.infoq.com/news/2010/09/java-on-azure-theory-vs-reality. Plus my earlier post on getting Jetty to work in Azure - https://blogs.msdn.com/b/dachou/archive/2010/03/21/run-java-with-jetty-in-windows-azure.aspx, which goes into a bit more technical detail on how a Java application can be deployed and run in Windows Azure.

Java in Windows Azure

So at the time of this writing, deploying and running Java in Windows Azure is conceptually analogous to launching a JVM and run a Java app from files stored on a USB flash drive (or files extracted from a zip/tar file without any installation procedures). This is primarily because Windows Azure isn’t a simple server/VM hosting environment. The Windows Azure cloud fabric provides a lot of automation and abstraction so that we don’t have to deal with server OS administration and management. For example, developers only have to upload application assets including code, data, content, policies, configuration files and service models, etc.; while the Windows Azure manages the underlying infrastructure:

- application containers and services, distributed storage systems

- service lifecycle, data replication and synchronization

- server operating system, patching, monitoring, management

- physical infrastructure, virtualization, networking

- security

- “fabric controller” (automated, distributed service management system)

The benefit of this cloud fabric environment is that developers don’t have to spend time and effort managing the server infrastructure; they can focus on the application instead. However, the higher abstraction level also means we are interacting with sandboxes and containers, and there are constraints and limitations compared to the on-premise model where the server OS itself (or middleware and app server stack we install separately) is considered the platform. Some of these constraints and limitations include:

- dynamic networking – requires interaction with the fabric to figure out the networking environment available to a running application. And as documented, at this moment, the NIO stack in Java is not supported because of its use of loopback addresses

- no OS-level access – cannot install software packages

- non-persistent local file system – have to persist files elsewhere, including log files and temporary and generated files

These constraints impact Java applications because the JVM is a container itself and needs this higher level of control, whereas .NET apps can leverage the automation enabled in the container. Good news is, the Windows Azure team is working hard to deliver many enhancements to help with these issues, and interestingly, in both directions in terms of adding more higher-level abstractions as well as providing more lower-level control.

Architecting for High Scale

So at some point we will be able to deploy full Java EE application servers and enable clustering and stateful architectures, but for really large scale applications (at the level of Facebook ad Twitter, for example), the current recommendation is to leverage shared-nothing and stateless architectures. This is largely because, in cloud environments like Azure, the vertical scaling ceiling for physical commodity servers is not very high, and adding more nodes to a cluster architecture means we don’t get to leverage the automated management capabilities built into the cloud fabric. Plus the need to design for system failures (service resiliency) as opposed to assuming a fully-redundant hardware infrastructure as we typically do with large on-premise server environments.

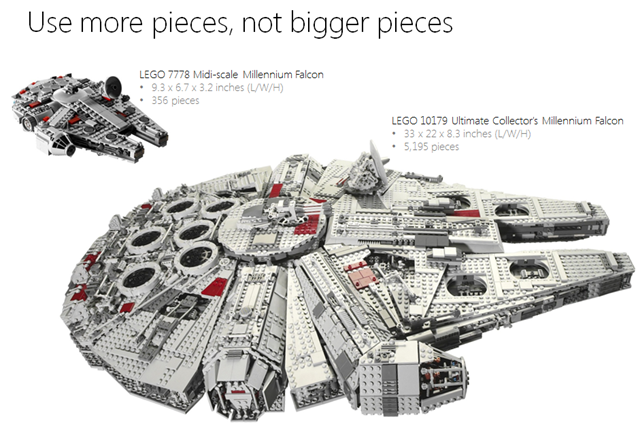

(Pictures courtesy of LEGO)

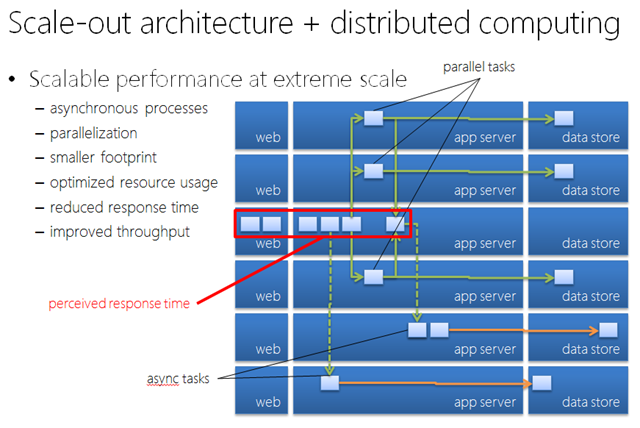

The top-level recommendation for building a large-scale application in commodity server-based clouds is to apply more distributed computing best practices, because we’re operating in an environment with more smaller servers, as opposed to fewer bigger servers. The last part of my JavaOne presentation goes into some of those considerations. Basically - small pieces, loosely coupled. It’s not like the traditional server-side development where we’d try to get everything accomplished within the same process/memory space, per user request. Applications can scale much better if we defer (async) and/or parallelize as much work as possible; very similar to Twitter’s current architecture. So we could end up having many front-end Web roles just receiving HTTP requests, persist some data somewhere, fire off event(s) into the queue, and return a response. Then another layer of Worker roles can pick up the messages from the queue and do the rest of the work in an event-driven manner. This model works great in the cloud because we can scale the front-end Web roles independently of the back-end Worker roles, plus not having to worry about physical capacity.

In this model, applications need to be architected with these fundamental principles:

- Small pieces, loosely coupled

- Distributed computing best practices

- asynchronous processes (event-driven design)

- parallelization

- idempotent operations (handle duplicity)

- de-normalized, partitioned data (sharding)

- shared nothing architecture

- optimistic concurrency

- fault-tolerance by redundancy and replication

- etc.

Thus traditionally monolithic, sequential, and synchronous processes can be broken down to smaller, independent/autonomous, and loosely coupled components/services. As a result of the smaller footprint of processes and loosely-coupled interactions, the overall architecture will observe better system-level resource utilization (easier to handle more smaller and faster units of work), improved throughput and perceived response time, superior resiliency and fault tolerance; leading to higher scalability and availability.

Lastly, even though this conversation advocates a different way of architecting Java applications to support high scalability and availability, the same fundamental principles apply to .NET applications as well.